Which Are Better: Mutual Funds or ETFs?

You’re probably familiar with mutual funds. They are arguably the most common type of investment choice for 401(k) and other retirement accounts. Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs), by contrast, have only been around since the early 1990s, and have not yet found their way into very many retirement plan menus. But they are widely available for brokerage accounts and since 2008 have been experiencing explosive growth. You may be wondering what the difference is between the two types of funds, and which makes a better investment.

ETFs, like traditional mutual funds, represent a basket of assets such as stocks or bonds. Unlike mutual funds, investors cannot buy ETF shares directly from the investment companies that offer them. Instead investors must buy ETFs from other investors, just like stocks. That has two implications: (1) you can buy ETFs anytime during the trading day, unlike mutual funds, which can only be bought at the end of the day after their NAVs have been calculated, and (2) during periods of high demand, the prices of ETFs can exceed the actual net asset value (NAV) of their underlying assets. Since buyers generally do not want to pay more than an ETF is worth, something is needed to keep the price close to the ETF’s NAV. The solution is to allow certain financial institutions known as authorized participants (AP) the ability to purchase and redeem blocks of ETF shares (called creation units) directly from the ETF company. This approach gives ETFs an arbitrage mechanism that tends to minimize the potential deviation between the market price and the NAV of the ETF’s shares. If there is strong investor demand for an ETF, its share price will (temporarily) rise above its NAV per share, giving APs an incentive to purchase additional creation units from the ETF and sell the component ETF shares in the open market. The additional supply of ETF shares reduces the market price per share, generally eliminating the premium over NAV. A similar process applies when there is weak demand for an ETF and its shares trade at a discount from NAV.

Creation unit purchases and redemptions are “in kind” – meaning the underlying assets are traded back & forth rather than bought & sold – allowing them to swap out low basis shares for high basis shares without having to pay tax. As a result, ETF proponents argue that ETFs are more tax efficient than mutual funds, which cannot do that.

Another professed benefit of ETFs is their lower expense ratios – the annual costs fund holders have to pay to the fund companies – as compared to mutual funds. While true in the aggregate, this is really due to the fact that the majority of ETFs are passively managed and based on indices created and updated by various other financial institutions. There are numerous examples of mutual funds in certain asset classes that are less expensive than their ETF counterparts.

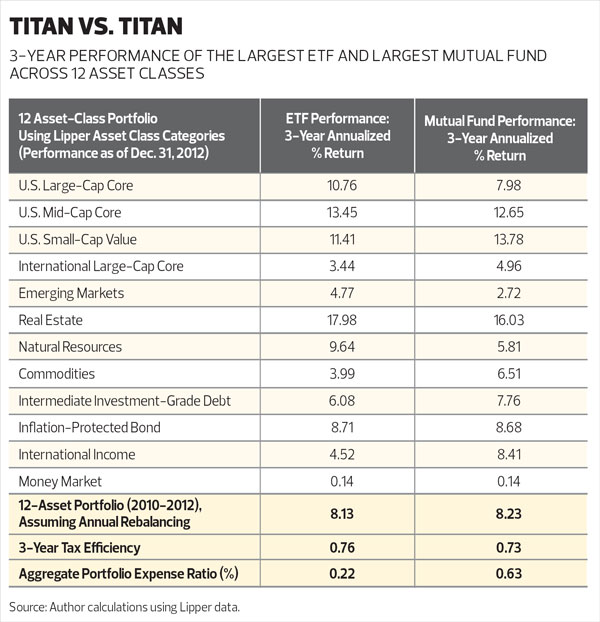

Craig Israelsen, associate professor at Utah Valley University, recently attempted to quantify the difference between mutual funds and ETFs by creating two portfolios – one using only ETFs and the other containing only mutual funds. Each portfolio was comprised of 12 asset classes: large-cap U.S. stocks, mid-cap U.S. stocks, small-cap value U.S. stocks, non-U.S. developed market stocks, non-U.S. emerging market stocks, real estate, natural resources, commodities, U.S. bonds, U.S. inflation-protected bonds, non-U.S. bonds, and cash. Each asset class was weighted equally at 8.33% of the total portfolio, and each portfolio was rebalanced at the end of each year over a three-year period.

To make the comparison as objective as possible, Israelsen selected the largest ETF and the largest mutual fund (in terms of total assets) to represent each of the above asset classes in the two portfolios. He did not attempt to identify the best-performing ETF or mutual fund. The returns as measured were net of expense ratios, and there was no attempt to take into account taxes, trading costs, or inflation. All data came from Lipper.

The results are shown on the chart below. Although the ETF portfolio had slightly higher tax efficiency and a considerably lower aggregate expense ratio (0.22% versus 0.63%), the two portfolios produced nearly identical returns in the three years from 2010 through 2012 (8.13% average annual return for the ETF portfolio and 8.23% for the mutual fund portfolio).

Of course, this analysis only covered a three-year period, a very small sample from which to infer longer-term investment performance. And there was a pretty big disparity in some of the individual asset classes, in particular international fixed income, where the mutual funds trounced the ETFs, and in natural resources, where the reverse occurred. Nonetheless, my conclusion from this analysis is that it’s more important to focus on building a well-diversified portfolio rather than trying to find the “best” mutual fund or ETF. Other studies have borne this out as well.

Israelsen also discovered that the performance spread among ETFs within each asset class tended to be smaller than that of the mutual funds. This, of course, can be attributed to the fact that most ETFs are index trackers, whereas many mutual funds are actively managed and have a lot more flexibility. But as to which is better, mutual funds or ETFs, the answer is neither, as long as you utilize a sufficient number of asset classes and an appropriate asset allocation model.